November 1, 2023

By Holly Smith

Photo by Suad Kamardeen, Unsplash

Photo by Suad Kamardeen, Unsplash

“It’s important to turn images into data, or we’re leaving a lot of data unused,” shared Anjali Adukia, assistant professor at the University of Chicago Harris School of Public Policy and the College and faculty director of the MiiE Lab (Messages, Identity, and Inclusion in Education).

Professor Adukia uses AI to research representation of age, race, and gender in award-winning children’s literature in both images and text. She and her team even won two Google awards–one for education and another for diversity, equity, and inclusion. “We live in a world where AI can get a bad reputation, so for AI to be used for social good gave a lot of hope to people. AI can be used in powerful ways to improve lives,” explains Adukia.

While she emphasizes that AI is as biased as the person who makes it, Adukia points out that computers can analyze color more consistently than humans (think of the dress) and that is why she and her team chose to use AI to help them analyze race and other characteristics in children’s books.

So how did Adukia and her team, including Alex Eble, Emileigh Harrison, H. Birali Runesha, and Teodora Szasz, approach this large task? First, they had to decide which books would be used in this work. They ultimately selected books that had won awards featured by the Association for Library Service to Children, a division of American Library Association, because these books are highly influential and a common feature of children's educational experiences. Winners of various book awards are often highlighted in school libraries, book fairs, catalogs, book clubs, and elsewhere. These award winners were classified as being in either the mainstream collection or the diversity collection. The mainstream collection includes books of “high literary” value and Newbery Medal and Caldecott Medal winners. The diversity collection is made up of books that center experiences of people of specific identities and are likely to be put on “diversity lists.”

Next, an AI model had to be trained. “The Research Computing Center (RCC) has been thought partners throughout this process,” said Adukia, “The RCC made sure that the computer science could happen. I learned about computational science tools from the computational scientist Teodora Szasz and RCC director Dr. H. Birali Runesha. They really kicked us off. It’s been an amazing partnership.”

While many AI models have been trained to do face recognition in photographs, the model designed by RCC had to learn to detect every face in illustrations, which are prominent in children’s literature. Next, the AI model was trained to classify, skin color, age, and gender.

Adukia also needed the RCC model to analyze text in order to identify characters’ race, age, and gender. The text was scanned for names to either match to a list of famous people or to Social Security data to determine the gender of the character. The text was additionally scanned for words that could signal gender (e.g. she), nationality (e.g. Kenyan), or age (e.g. boy).

Using the AI model, Adukia’s team found that mainstream books show lighter skin even after conditioning on race. In fact, compared to their portion of the US population, Black and Latine people are underrepresented in images and text. Additionally, no matter the data source, males, especially White males, are more likely to be represented. Females, on the other hand, are more likely to appear in images than in text (to be “seen” rather than “heard”).

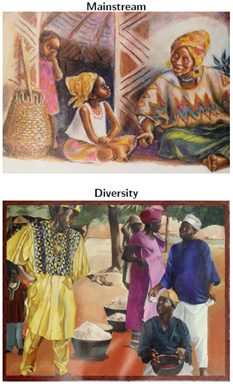

An example of the difference in skin tones as portrayed in the mainstream versus the diversity collection

The most surprising finding to Adukia was that children are systematically shown with lighter skin than adults. It is unclear that this should be a systematic pattern; indeed, older adults may be more likely to have lighter skin tones because melanin breaks down over time. Adukia wonders if our culture tends to equate youth with innocence and innocence with lightness. She notes that this should be explored in future work.

Adukia and her team additionally examined how characters of different races and genders are portrayed. They found that Black females are more associated with struggle and the performing arts, Black males with sports and struggle, White females with family and performing arts, and White males with power and business.

In extensions of this work, Adukia and other members of her team Callista Christ, Anjali Das, and Ayush Raj, also noticed changes over time. A century ago, women were less positively spoken about than men, but the depiction of sentiment related to females and males has converged over time. This convergence, while promising, masks the disparity in portrayal across race: White women are more often portrayed positively while Black women are more often portrayed negatively. Furthermore, while differences in sentiment associated with Black people and White people have decreased over time, a gap remains.

Next up for Adukia and her team: textbooks. “In the curricular content, what are the messages that are sent to kids? Whose voices are the curriculum reflecting? I often joke that I've been working on this since I was a child. I grew up in small towns in the US and I didn't see myself in books. It’s always been in the back of my mind.”